Air power was crucial to the outcome of the Burma Campaign. In 1942 and 1943, the Allies depended on traditional supply lines. Not only was it vulnerable to being cut by the Japanese, supply by road was always precarious in Burma because the few roads were poorly maintained and quickly turned into glutinous quagmires during the long monsoon season.

These crippling limitations were overcome by using air power to keep troops supplied with food, water, ammunition and fuel, even when cut off. The potential of this strategy was confirmed with Chindit columns in 1943. The Battle of Admin Box then demonstrated, for the first time, that adequate supplies for an entire division could be delivered by air. To achieve this remarkable feat, it was necessary to clear the Japanese from the sky over the drop zone, as the transport planes had minimal armament. Key to establishing air superiority was the arrival of spitfires, which could outperform the Japanese fighters. Once the Allies had control of the air, they could use their huge fleet of transport aircraft to relocate units rapidly and keep them supplied. This capacity was decisive in the Battles of Kohima and Imphal in 1944 and in retaking Burma in 1945.

Establishing Air Superiority

The mainstay of the Allied fighter force in 1943 was the Hawker Hurricane, which was hardy and quite evenly matched against the Oscar (Nakajima Ki-43), the principal fighter of the Japanese army. However, it could not fly as high or as fast as the Dinah (Mitsubishi Ki-46) reconnaissance aircraft.

The game-changer was the arrival in late 1943 of brand-new Spitfires, which could fly faster and higher than Hurricanes and also had a greater rate of climb. “Flies like a bird” wrote Flight Sergeant Dudley Barnett of 136 Squadron, after his first flight in October 1943 (1). The Spitfires were also more heavily armed and provided a significant boost to morale.

Air Transport

A huge fleet of British and American transport aircraft had been gathered in India to carry supplies to China. This a priority to sustain China in her war with Japan, a war that tied down a million Japanese troops. Before the fall of Burma, supplies had been conveyed via the port of Rangoon and then overland along the Burma Road. When this route was closed, they were flown from India over the Himalayas, a hazardous journey known as the “Hump”.

The strategic decision to supply troops by air was possible because of the huge transport capability available in India. The Battle of Admin Box established that the strategy was viable, fully sustaining the 7th Indian Division despite being entirely cut off for 18 days. This emergency needed American aircraft to be diverted from the Hump, to the displeasure of President Roosevelt.

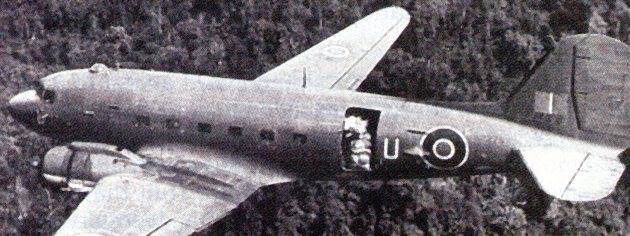

The workhorse of the transport fleet was the Douglas C47 Dakota, which could carry almost 4 tons. It was a military version of the pre-war DC3 airliner. Ten thousand Dakotas were built in the USA during WW2 and the first of over 1900 received by the RAF arrived in India in 1942.

Dropping cargo from a pitching plane was difficult and dangerous, as it involved thrusting heavy packages from an open side hatch. In the image below of crew struggling to push their supplies out of a C47 over Burma, a ‘kicker’ can be seen lying on his back and pushing with both legs.

During the siege of Kohima, when the garrison was isolated & surrounded by Japanese, attempts were made to deliver supplies by parachute. Squadron Leader Peter Bray of 31 Squadron RAF, flying Dakotas from Assam to deliver supplies, described the routine:

“Take off would be around dawn at 6 a.m. Flying eastwards one would see the paddy fields soon replaced by the inhospitable … Chin Hills running in ridges north to south, rising at first to a few hundred feet & gradually to 6,000 feet, each ridge with a correspondingly deep valley, much of which was covered by deep jungle.” (3)

“Briefing before take-off was provided by an Army Liaison Officer who defined the DZ with great care so that we would be able to find it from some prominent feature on our large-scale map. DZ code letters were given to prevent supplies going to false DZs created by the Japs. The pilot would make a straight approach on the DZ giving the ‘stand by’ light to the dropping crew in the back of the aircraft, followed by the ‘drop’ light when he judged the aircraft position to be right. When the load was clear, the pilot made a steep turn to the left to observe the accuracy of the drop so as to know the correction to make for the subsequent drops.” (3)

Once the Japanese had cut the road from Kohima on March 29, air transport was the only option for supplying 4 Corps at Imphal until the road was finally reopened on June 22. During that time, Operation Stamina flew in 540 tons of supplies each day.

There were 6 airfields around Imphal, but only 3 of these were all-weather. The primary one was Imphal Main, a few miles north of Imphal town.

In addition to air drops of supplies, the transport fleet was also able to rapidly airlift troops across long distances. To meet the crisis of the Japanese invasion of India in March 1944, the allies flew 5th Indian Division into Imphal & Dimapur. Detailed plans for this unprecedented operation had been prepared in advance & it was achieved without a hitch, between March 17 & 29. Transferring each of the three brigades required 260 Dakota sorties. After 5th Division, 7th Indian Division was transferred in the same way.

For most of the troops, it was the first time they had ever flown. One of them was Private Ray Street, who later recalled:

“It wasn’t a good advert for flying. It wasn’t very comfortable. There weren’t any seats. We had to sit on our packs. The crew were American. They had parachutes. We didn’t. When we asked why, they said it was their plane! The navigator kept poking his head out telling us that if we saw any Japs to put the Bren guns out of the windows and shoot them.” (6)

As well as the men, vehicles, guns & mules were transported. Return flights carried 43,000 non-combatants & 13,000 casualties out of the war zone.

By the end of the Battles of Kohima and Imphal, the RAF had carried 19,000 tons of supplies, 12,000 troops and 13,000 casualties. The air and ground crews were exhausted.

Ground Attack

As well as its combat role, the versatile Hurricane was also widely used to support ground forces by attacking Japanese troops, vehicles, bridges and railways. For this role, it carried two 250lb bombs and was referred to as a Hurribomber.

Four squadrons of Vultee Vengeance dive bombers provided further punch to air strikes during the Battles of Imphal and Kohima.

RAF Roundels

The red circle in the centre of the RAF roundel led to friendly fire incidents when it was mistaken for the red sun symbol on Japanese planes. Consequently, it was removed from most RAF aircraft by 1944. This is illustrated by the painting below of Hurribombers in their ground attack role.

Quotations are cited from:

(1) “Burma ’44” by James Holland (2016) Transworld Publishers.

(3) “Japan’s Last Bid for Victory” by Robert Lyman (2011) Praetorian Press.

(6) “The Siege of Kohima” by Robert Street (2003) Barny Books.