The Naga in 1944

Kohima sits at 4,137 feet in the Naga Hills, a vast and inhospitable region of jungle-covered hills with few roads. In 1944, it was sparsely inhabited by scattered aboriginal tribes, most of whom had been converted from animism by American Baptist missionaries. They traditionally practiced head-hunting, although this was discouraged under British administration.

British soldiers were struck by their appearance; they were described as “like Red Indians” by Ray Street of the Royal West Kents.

Naga Support for the British

The Nagas of Kohima provided invaluable support to the British, acting as guides, spies, porters & stretcher-bearers, as well as combatants if provided with rifles.

One of these exotic allies, Rhizotta Rino, explained their support:

“Why did we fight for the British? They were our protectors. They were here before the Japanese and they protected us. We had to help them”.

Major General Grover, Commander of the British 2nd Division, wrote:

“They offer to take on any job, usually of an Intelligence nature, to visit some village behind Jap lines, or to provide porters or guides whenever required, and offer to do all this for nothing. We are insisting on paying them. One has been taught to regard the Nagas as savage head-hunters. Some of them are, but the great majority are extremely lovable.”

Harry Swinson of the 7th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment described Naga stretcher bearers bringing British wounded from 5 Brigade in April 1944:

“It was a precarious journey as a heavy shower of rain had rendered the precipitous tracks unnegotiable. The doctors were full of praise for the conduct of the Nagas. When the odd mortar bomb came over, they had put the stretchers down under cover & fanned the wounded men with branches till they could move on again. A great show this. I could see the [Medical Officer] was pleased. Had the Nagas shown they couldn’t take it, a most difficult situation would have arisen; there aren’t enough troops to do the job.” (3)

Homeless

Hundreds of the Naga were displaced by the war. As the armies moved away, they were able to return to their villages that had been caught in the battle zones. The poignant recollections of Neidelie, aged thirteen, have been recorded:

“We were elated at the thought of going back home. But on the way back, we saw many dead Japanese soldiers … After some time, I grew tired of counting & looking at the dead soldiers, all of whom looked alike now that they were bloated & decomposing by the roadside.

The group that we were travelling with was a large body of our villagers, so we buried the dead bodies when we came upon them on our way. But after some time, we gave up this effort because there were just too many dead Japanese for us to bury all … Dead bodies were strewn over the countryside & the stench from the bodies was more than anyone could bear.” (3)

Several Naga villages that had been occupied by the Japanese had been completely destroyed by Allied shelling & bombing, such as the one at Kohima.

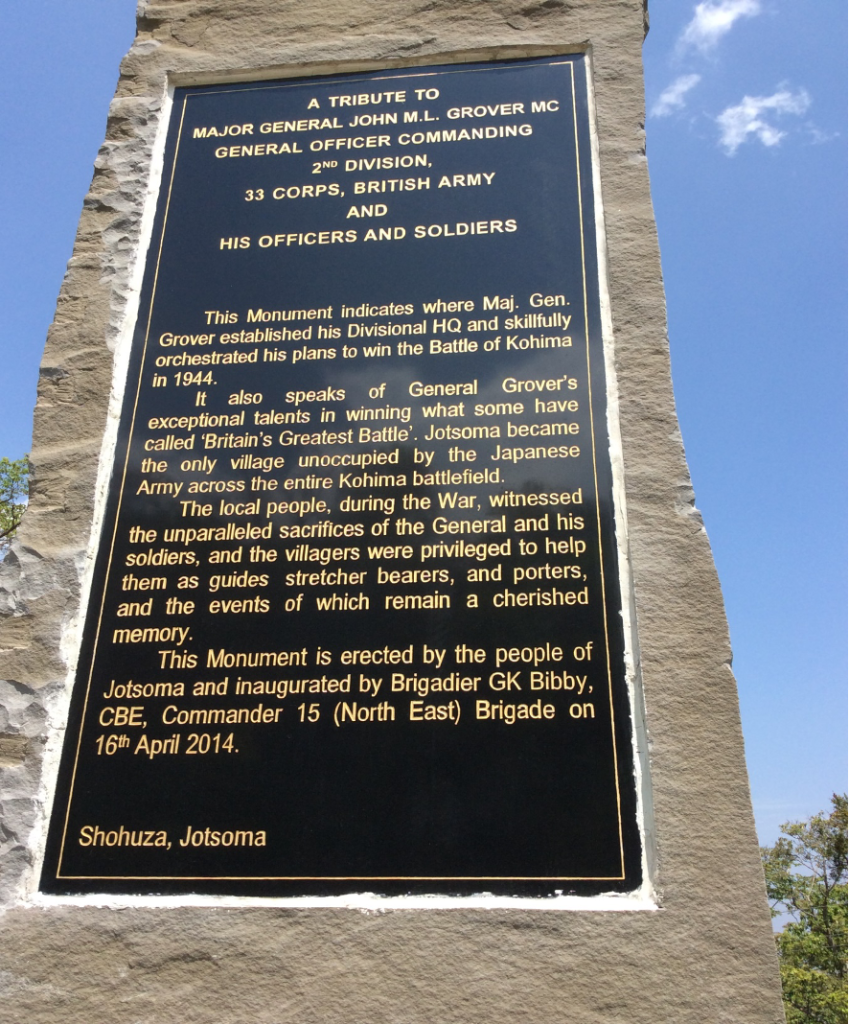

The Grover Monument

In 2014, citizens of the Naga village at Jotsoma dedicated a monument to Major General Grover, his officers and soldiers. The general’s daughter-in-law Mrs Celia Grover was present.

Kohima Educational Trust

The Kohima Educational Trust was created in gratitude to the Nagas for their staunch support. Its purpose is to help finance the education of Naga children through scholarships, prizes and the provision of educational resources, using the past to benefit the future.

A film describing the experiences and perspectives of Naga who remember 1944 can be found here.